Born from Dust, Dying in Glory: The Epic Life Cycle of Stars

Introduction

Stars, the glowing beacons of our night sky, may seem eternal, but like all things in the universe, they too have a life cycle—a journey that begins in vast clouds of gas and dust and ends in spectacular transformations. From their quiet birth in stellar nurseries to their dramatic deaths as white dwarfs, neutron stars, or black holes, stars undergo a series of stages shaped by mass, temperature, and nuclear processes. Understanding this life cycle not only reveals the story of stars themselves but also offers insight into the cosmic origins of the elements that make up our world—and us.

|

| The Pillars of Creation: A Stellar Nursery in the Eagle Nebula Image Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, and STScI; processing by Joseph DePasquale, Anton M. Koekemoer, and Alyssa Pagan (STScI) |

Stellar Origins: From Dust to Fusion

Birth in a Cloud: The Stellar Nursery

All stars begin in nebulae—vast clouds of gas and dust scattered across galaxies. These clouds are cold and dark, made mostly of hydrogen, the most abundant element in the universe.

Over time, gravity begins to pull parts of a gas cloud together. As the material collapses inward, the center becomes denser and hotter, forming what is known as a protostar — the earliest stage in a star's life. This process can take millions of years, quietly shaping what will eventually become a luminous star.

However, not all collapsing gas clouds are massive enough to sustain the intense pressure and temperature needed to ignite nuclear fusion. In such cases, they remain as failed stars — known as brown dwarfs, or large gas giants like Jupiter in our own solar system. These objects shine faintly (if at all), and never reach the true stardom of fusion-powered light.

Ignition: The Birth of a True Star

As the protostar contracts, temperatures at its core rise dramatically. When the core temperature hits about 10 million Kelvin, hydrogen atoms begin to fuse into helium—releasing vast amounts of energy.

This marks the start of nuclear fusion and the star officially enters the main sequence phase, the longest and most stable part of its life. The pressure from the energy released by fusion pushes outward, balancing the inward pull of gravity. The star is now in hydrostatic equilibrium, shining steadily for millions or even billions of years.

The Fusion Cycle: From Hydrogen to Iron

During the main sequence, the star continuously fuses hydrogen into helium in its core. This process provides the energy that makes the star shine. This is the current state of our Sun. But hydrogen won’t last forever.

Once the hydrogen in the core is exhausted, the delicate balance between gravity and outward pressure from fusion breaks. The core contracts under gravity, causing its temperature and pressure to rise sharply.

At this higher temperature, the star ignites helium fusion, converting helium into carbon and oxygen. This marks the beginning of a new phase in the star’s life.

In more massive stars, the core gets hot enough to continue the fusion chain:

-

Carbon → Neon

-

Neon → Oxygen

-

Oxygen → Silicon

-

Silicon → Iron

Each stage creates heavier elements, but releases less energy than the previous one. Eventually, the core builds up iron (Fe). Fusion stops at iron because fusing iron consumes energy rather than releasing it. Without energy to counteract gravity, the star is now on the brink of a catastrophic end.

However, not all stars go through every fusion stage. If a star’s mass is not high enough, its core won’t reach the temperatures needed to fuse heavier elements. Such stars may stop at helium or carbon fusion and end their lives.

Destined by Mass: Peaceful or Explosive Ends

A star’s final fate is written in its mass. Depending on how massive a star is when it begins its life, it can meet a peaceful end or go out with a cosmic bang.Low-Mass Stars: Less than ~0.5 solar masses

These stars, often called red dwarfs, are the smallest and most efficient stars in the universe. They burn their hydrogen fuel very slowly and can shine for trillions of years—far longer than the current age of the universe.

Because their cores never reach the extreme temperatures needed to fuse helium, red dwarfs don’t evolve into giants. Instead, they gradually cool and dim over time. When they finally run out of hydrogen, they simply fade into cold, dark white dwarfs. Over unimaginably long periods, they may become black dwarfs—invisible remnants that no longer emit light. However, since the universe is not old enough, no black dwarf exists yet.

These stars do not undergo dramatic ends, and they do not produce or eject heavy elements. Their legacy is in their stability, not in cosmic fireworks.

Medium-Mass Stars: About 0.5 to 8 solar masses

Stars like our Sun live for billions of years by fusing hydrogen into helium in their cores. When hydrogen runs out, the core contracts and heats up, allowing the fusion of helium into carbon and oxygen. Meanwhile, the outer layers expand, and the star becomes a red giant.

Eventually, the helium runs out, and fusion in the core stops. The star, now unstable, begins to shed its outer layers. But unlike massive stars that end in violent explosions, stars with about 0.5 to 8 solar masses die gently.

As the core contracts, the outer layers expand and become loosely bound due to weak surface gravity. Over thousands of years, stellar winds and pulsations slowly blow these layers away — not as an explosion, but as a gradual outflow of gas. This ejected material forms a planetary nebula: a glowing, colorful shell of gas, illuminated by intense ultraviolet radiation from the hot, dense core left behind.

At the heart of the nebula lies a white dwarf—a dense, Earth-sized stellar remnant made mostly of carbon and oxygen. It has no fuel left to burn, and will simply cool and fade over billions of years.

During this quiet farewell, the star returns carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen—produced during its life—to the interstellar medium. These elements enrich the galaxy and become the building blocks for new stars, planets, and life. There’s no supernova here—just a graceful exit, painting the sky with soft light and cosmic chemistry.

High-Mass Stars: About 8 to 25 solar masses

High-mass stars burn bright and live fast. After exhausting hydrogen and helium, their cores become hot enough to fuse heavier and heavier elements—carbon, neon, oxygen, and silicon—until they produce iron. At that point, fusion becomes a losing game. Iron doesn’t release energy when fused; instead, it consumes energy, so no further fusion is possible.

Core to collapse under its own gravity. This sudden collapse triggers a core-collapse supernova, a titanic explosion that tears the star apart in milliseconds. The outer layers are blasted into space, while the core is crushed into a neutron star—a city-sized object so dense that a teaspoon of it would weigh billions of tons.

The supernova not only creates but also ejects elements like oxygen, silicon, iron, gold, silver, and even uranium, enriching the surrounding space. These explosions are responsible for many of the elements found on Earth and in our bodies.

Very High-Mass Stars: About 25 to 100 solar masses

When stars are even more massive, their lives become more chaotic and unstable. These giants often pass through extreme phases such as Wolf–Rayet stars—hot, stripped-down stars that have lost their outer hydrogen layers and expose heavier elements like helium, carbon, or oxygen. Others become luminous blue variables (LBVs), massive, hot stars that experience unpredictable outbursts, rapid mass loss, and brightness changes due to internal instability.

These stars shed a significant portion of their mass through intense stellar winds and eruptions, preparing them for a dramatic finale. Inside, they fuse elements in a similar chain—up to iron—until fusion can no longer continue.

Their deaths can result in a hypernova, a more energetic version of a supernova, especially if the star has high rotation or strong magnetic fields. The core collapses past the neutron star stage into a black hole—an object so dense that not even light can escape.

These explosive deaths release vast amounts of energy and are responsible for creating the heaviest elements in the universe, including gold, platinum, and uranium. The debris from these cataclysms spreads across galaxies, seeding new generations of stars, planets, and potentially life.

Extremely Massive Star: Over 100 solar masses

The most massive stars—those over 100 solar masses—end their lives in an extraordinary way known as a pair-instability supernova. In their cores, intense gamma rays normally provide radiation pressure that balances the crushing force of gravity. But at extremely high temperatures, these gamma rays begin to convert into electron–positron pairs, reducing that crucial pressure. This sudden imbalance causes the core to collapse inward, triggering explosive fusion of oxygen and silicon that releases an enormous amount of energy. The explosion is so powerful that no remnant is left behind—not even a neutron star or black hole. All the star’s material is blasted outward in every direction, never falling back, and enriching the universe with heavy elements like gold and platinum. The star is truly obliterated, leaving only a cloud of glowing stardust drifting through space.

In other cases, if the star is too massive, gravity wins completely, and the star collapses directly into a black hole—without even a supernova explosion.

These rare events are powerful enough to eject vast quantities of heavy elements and may have played a crucial role in enriching the early universe with metals during the time of Population III stars.

Stellar Afterlives: Exploring the Universe's Most Fascinating Final Acts

Red Giants: The Swollen Hearts of Aging Stars

A Red Giant marks the beginning of the end for medium-sized stars like our Sun. After spending billions of years steadily fusing hydrogen into helium in the core, the star eventually runs out of hydrogen fuel at its center. With fusion no longer providing pressure to counteract gravity, the core contracts and heats up. Meanwhile, hydrogen in the surrounding shell—just outside the core—reaches high enough temperatures to ignite shell burning. This shell fusion is more energetic than core fusion ever was, because it occurs in a thinner, denser layer under stronger gravity. The intense energy released pushes outward, causing the star’s outer layers to expand enormously.

The transformation is dramatic. A star that was once the size of the Sun can swell to hundreds of times its original diameter. Despite its bloated size, the surface cools and reddens, giving the star a characteristic reddish glow with a lower temperature of about 3,000 to 5,000 Kelvin. The star becomes much more luminous and starts losing mass through stellar winds, slowly shedding its outer envelope.

Eventually, the contracting core becomes hot enough for helium fusion to ignite in a flash, converting helium into carbon and oxygen. But even this second wind is temporary. Once the helium is exhausted, the star can no longer support itself. The outer layers drift away into space, forming a glowing planetary nebula, while the leftover core settles into its final stage as a white-hot ember: the White Dwarf.

White Dwarfs: The Glowing Embers of Dead Stars

What remains after the Red Giant sheds its outer envelope is a White Dwarf, the dense core left behind. With fusion now completely stopped, the star doesn’t generate energy in the usual sense. Instead, it is supported against collapse by a strange form of quantum pressure called electron degeneracy pressure, a result of the Pauli exclusion principle, which states that no two electrons can occupy the same quantum state.

White Dwarfs are tiny—roughly the size of Earth—but their mass can be over half that of the Sun. This makes them incredibly dense: a single teaspoon of white dwarf matter would weigh tons. Although they are no longer undergoing fusion, they remain extremely hot—often above 100,000 Kelvin when newly formed—and glow brilliantly, emitting ultraviolet and even X-ray radiation in some cases.

With no new source of energy, a white dwarf begins a slow process of cooling and dimming. Over billions of years, it will fade from view entirely. But in the current age of the universe (13.8 billion years), none have yet had enough time to fully fade. When they do, they will become something even more ghostly: Black Dwarfs.

Black Dwarfs: Theoretical Corpses of White Dwarfs

A Black Dwarf is a theoretical object—the final evolutionary state of a white dwarf once it has cooled down enough to no longer emit light or heat. This process takes trillions of years, far longer than the current age of the universe. Therefore, no black dwarfs exist yet, but they are expected to populate the universe in the far future.

These objects would be cold, dark, and invisible—composed of carbon and oxygen in a crystalline form, like massive cosmic diamonds floating through space. Though lifeless, black dwarfs may eventually participate in exotic interactions, such as mergers or collisions, reigniting brief bursts of energy or even triggering a type of supernova.

Supernova: The Violent Death of Massive Stars

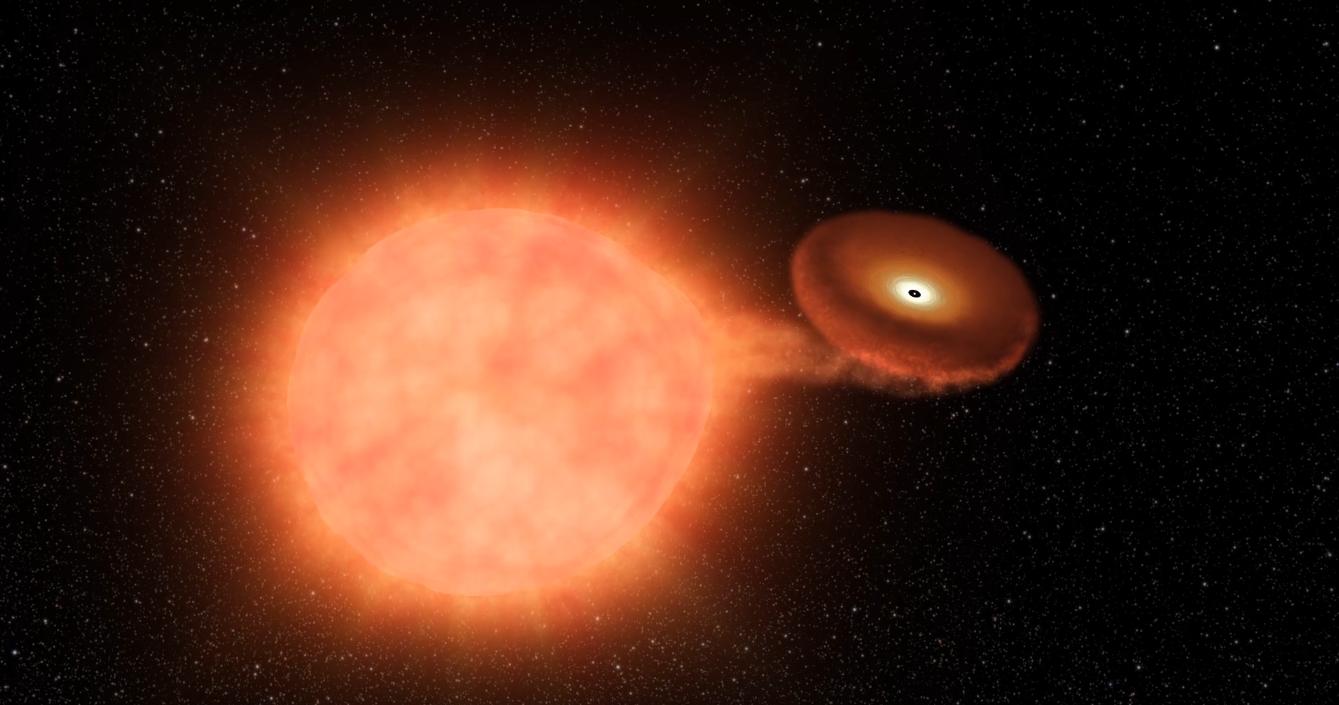

|

| This frame from an animation shows a gigantic star exploding in a "core collapse" supernova. Image Credit: NASA |

For stars more massive than about eight times the mass of our Sun, death is not peaceful—it is explosive. When such a star runs out of nuclear fuel, its iron core—no longer able to support itself—collapses catastrophically in less than a second, often in just a few hundred milliseconds. The inner layers of the star fall inward at up to 70% the speed of light, driven by gravity’s overwhelming force.

The core’s collapse creates an incompressible wall of neutrons—a newly formed neutron star. As the in-falling material crashes into this dense core, it rebounds outward, generating a titanic shockwave that blasts through the outer layers of the star. The result is a supernova, one of the most powerful events in the universe. For a brief moment, the exploding star can outshine an entire galaxy, and its brilliant glow can remain visible for weeks or even months, slowly fading as the ejected material expands and cools.

Within this violent explosion, the extreme pressure and neutron density trigger a process called the r-process (rapid neutron capture process), where atomic nuclei rapidly absorb neutrons to form very heavy, neutron-rich elements like gold, platinum, and uranium—within just seconds. These newly created heavy elements are then ejected into space by the shockwave, along with iron, oxygen, and silicon, seeding the surrounding galaxy with the raw materials for future stars, planets, and possibly life itself.

Meanwhile, the fate of the collapsed core depends on its mass. If it remains under a certain limit, it becomes a neutron star. If the mass is too great, gravity wins again, and the core collapses further into a black hole, an object so dense that not even light can escape its grasp.

Neutron Stars: The Densest Matter in the Universe

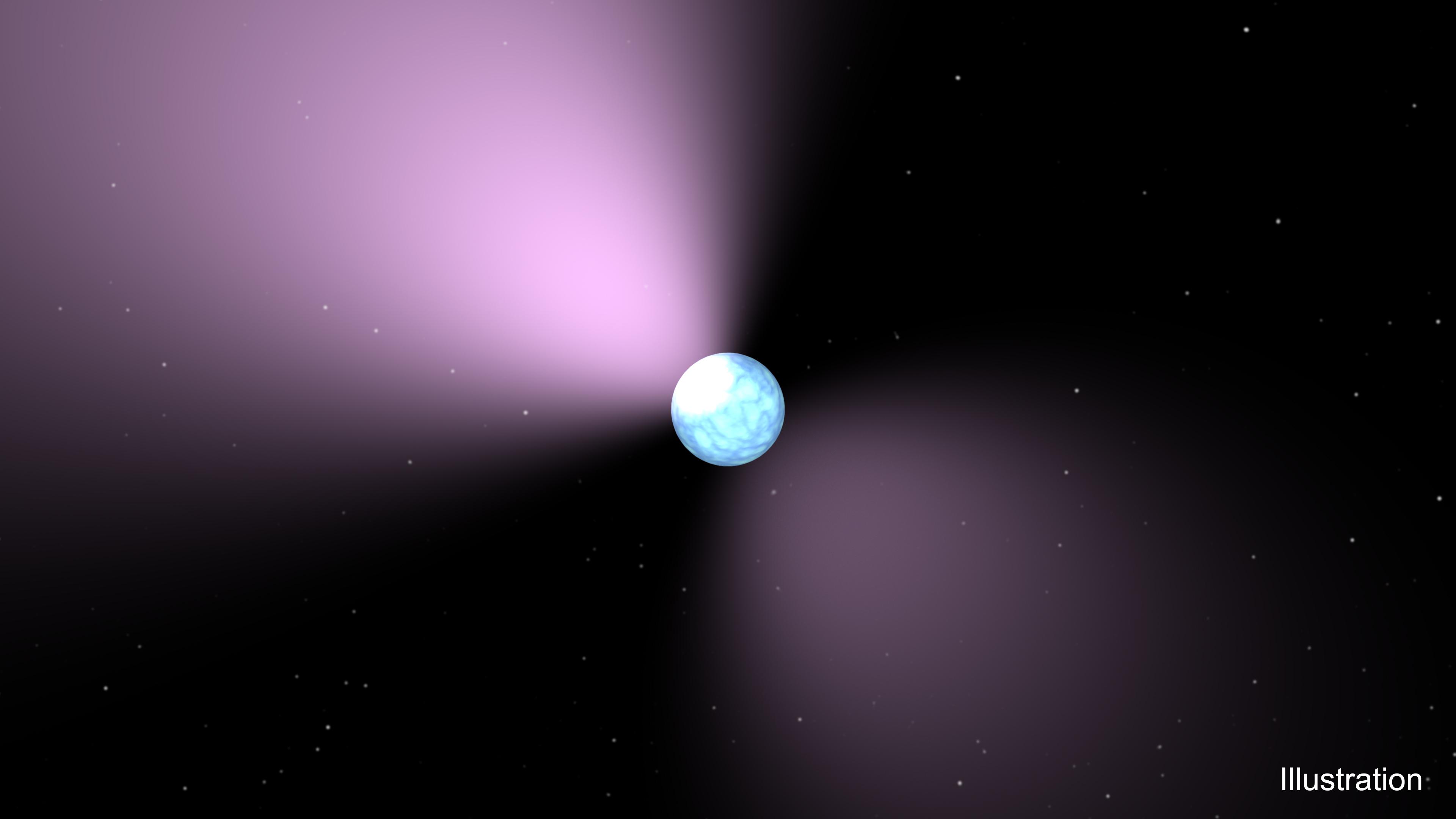

This artist's concept shows a pulsar, which is like a lighthouse, as its light appears in regular pulses as it rotates. Image Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech |

If the collapsed core of a supernova is between about 1.4 and 3 times the mass of the Sun, it becomes a Neutron Star. These bizarre objects are so dense that protons and electrons merge into neutrons, creating an object composed almost entirely of neutron matter.

A typical neutron star is no more than 20 to 25 kilometers across, yet it contains more mass than the Sun. One teaspoon of neutron star matter would weigh about a billion tons. The surface temperature can exceed 600,000 Kelvin. Neutron stars are born hot and spin incredibly fast—often hundreds of times per second. Some emit beams of radiation from their magnetic poles, creating a lighthouse effect as they spin—these are called pulsars.

Though invisible to the naked eye, neutron stars are detectable through their radio pulses, X-ray emissions, and the gravitational waves they may emit when they collide. They represent matter in one of its most extreme states—just one step before total collapse.

Black Holes: Where Time and Space Collapse

|

| This computer-simulated image shows a supermassive black hole at the core of a galaxy. Image Credit: NASA |

When the core remnant of a collapsing star is too massive—even neutron degeneracy pressure cannot stop its collapse. In this case, gravity overwhelms all known forces, crushing the core further and creating a Black Hole.

Black holes form when the core mass of a dying star exceeds about 2.5 to 3 times the mass of the Sun. At this point, there’s no known force in physics that can resist the collapse. The resulting black hole compresses that enormous mass into an incredibly small volume—often with a radius of just a few kilometers. For example, a black hole with the mass of our Sun would have a radius (Schwarzschild radius) of just about 3 kilometers.

Black holes have no solid surface. Instead, they are defined by the event horizon—an invisible boundary beyond which nothing can return, not even light. Inside this boundary lies the singularity, a point of infinite density and zero volume, where the known laws of physics cease to apply.

Only stars that begin their lives with more than 20 to 25 solar masses are likely to end up as black holes. Their cores are massive enough after a supernova to collapse all the way past the neutron star stage.

Often, black holes are surrounded by an accretion disk—a rapidly spinning, flattened disk of infalling gas, dust, and stellar debris. As this matter spirals closer to the black hole, it becomes compressed and heated to millions of degrees, emitting intense X-rays and gamma rays before crossing the event horizon. These high-energy emissions help astronomers detect black holes, even though the black hole itself remains invisible.

In recent years, astronomers have also observed gravitational waves—ripples in spacetime—produced by colliding black holes, offering a new way to "listen" to the universe and detect these mysterious giants.

Black holes are silent, invisible, and profoundly mysterious—the final, unescapable chapter in the lives of the most massive stars.

The Star Generations: Population III to I

The Three Generations of Stars

As we explore the life cycle of stars, it's important to understand that not all stars are the same. Astronomers classify them into three broad “populations” based on their age, chemical composition (metallicity), and location in the universe. These are known as Population III, Population II, and Population I stars. Each type tells a different chapter of the universe’s story.

Population III Stars: The Primordial Giants

Population III stars are believed to be the very first stars formed after the Big Bang—essentially the universe’s pioneers. They were born from clouds of pure hydrogen and helium, the only elements created in the Big Bang.

-

Metallicity: Virtually zero – no elements heavier than helium.

-

Age: Formed over 13 billion years ago.

Life: few million years

-

Mass: Thought to be extremely massive, many over 100 times the mass of the Sun.

-

Fate: Burned out quickly(in few Millian years) and ended in violent supernovae, spreading the first heavy elements across the cosmos.

Although we’ve never directly observed a Pop III star, their existence is predicted by theory and simulations. Without them, the universe would lack the metals needed to form future generations of stars and planets.

Without heavier elements (which help cool gas clouds and regulate star formation), these stars often formed with enormous mass, some reaching hundreds of times the mass of our Sun. Higher mass means higher gravity and higher temperature.

Fusion reactions (like proton–proton chain or CNO cycle) are extremely temperature-sensitive.

-

The rate of fusion, , increases with temperature roughly as:

Fusion rate ∝ T⁴ to T¹⁸

depending on the type of fusion (proton-proton chain vs. CNO cycle).

This is the reason why Population III stars quickly finish fusion reaction.

Population II Stars: The Cosmic Elders

Born from the enriched remains of Pop III supernovae, Population II stars contain small amounts of heavier elements (called "metals" in astronomy). These stars are ancient, often found in globular clusters and the halos of galaxies.

-

Metallicity: Low, but non-zero – includes elements like carbon and iron.

-

Age: 10 to 13 billion years old.

-

Location: Found in the halo of the Milky Way, globular clusters, and the galactic bulge.

-

Importance: Their chemical signatures help us understand how the early universe evolved chemically.

Many of the stars we see in old star clusters are Pop II, still burning quietly billions of years after their formation.

Population I Stars: The Modern Generation

These are the youngest stars, including our Sun. Formed from clouds enriched over billions of years by countless generations of exploding stars, Population I stars are rich in metals.

-

Metallicity: High, with abundant heavier elements.

-

Age: Typically a few billion years old.

-

Location: Found in the disks and spiral arms of galaxies.

-

Notable Examples: The Sun and most of the stars in the night sky.

-

Why They Matter: Their metal-rich environments make them more likely to have planets—and possibly life.

These stars continue the cosmic cycle, eventually returning material to the interstellar medium to form new stars and planets.

Conclusion: The Eternal Cycle of Starlight

The life of a star is nothing short of a cosmic epic—beginning as a silent whisper in a dark gas cloud, growing into a brilliant beacon of fusion, and ending in forms as varied as glowing embers, spinning corpses, or even invisible voids that warp space itself. From humble hydrogen to radiant red giants, and from spectacular supernovae to mysterious black holes, each stage reveals the dynamic, ever-evolving nature of our universe.

But beyond the physics lies a deeper truth: stars are the universe’s great recyclers. They forge the elements, illuminate galaxies, and in their death, spread the building blocks of life. Every atom in our bodies was once part of a star that lived and died billions of years ago.

To understand the life cycle of stars is to understand our own origins. We are, quite literally, children of the stars—woven from their light, shaped by their death, and carried forward by their legacy. In every sunrise, in every spark of gold, and in every breath of oxygen, the story of a star continues to shine.

Note: Images used in this blog may be illustrative, artistic, or imaginary and are not necessarily accurate in scale, shape, color, or structure.

Note: Assistance from a language model (LLM) was used in the creation of this blog for information gathering, paraphrasing, and correction of spelling and grammar.

An awesome read about the journey of the types of stars in our universe 💯

ReplyDelete